Train Your Brain: Exercises

Train Your Brain is a model to help understand and regulate your emotions:

In what follows you will find a range of exercises to help you manage your emotions and navigate your life. We hope you find them helpful. Not all ideas suit everyone, or make sense to everyone, so please feel free to pick and choose the things that work for you.

Self soothing

Realistic Expectations

Like any learning process, learning new ideas and skills can be difficult. We may struggle with attention, concentration, memory, energy or motivation. It can be tempting when learning something new to be a little impatient, perhaps expecting too much too soon and set the bar too high.

We then strive towards our target, but fall short and conclude we have failed. This can quickly lead to feelings of hopeless and frustration, and rather than spurring us on to do better next time, we are more likely to become demotivated and give up.

On a neurological level, if we aren’t reaching the standards set by others or ourself, we often get a release of the stress hormone cortisol, and an excessive amount of this certainly doesn’t help us learn!

If on the other hand, we set the bar within reach and achieve what we set out to achieve, we get a release of Dopamine, which is the very chemical that helps us feel motivated and energised.

The concept of dynamic goal setting can be useful to ensure our goals are helpful

If your goal is to be physically active and get into running, there will be various obstacles you will come up against in keeping up your exercise, that may vary from day to day. For example cold, wet windy weather, how much you have slept, the presence of aches and pains etc.

On a day when there are few obstacles, it may be realistic to set yourself a goal of running a few miles and you get the neurochemical boost of this as well as the dopamine release for reaching your goals.

If the next day, you haven’t slept well and feeling more achy, maybe a more realistic goal would be a 1 mile fast walk, and even if the cardiovascular boost might be less than a longer run, you get a dopamine boost and prevent adding more stress-hormones by falling short of your goal.

Breathing

-

Breathing can be a very effective tool

in regulating our stress levels. As described previously, when the limbic system in our brain has detected a potential threat, it immediately prepares a fast get away response by pumping oxygen into our big muscle groups.

This is clearly beneficial if we are faced with an immediate physical threat that we need to get away from.

-

However,

for most of us the kind of threats that activates this fight- flight-freeze response is of a psycho-social nature (a criticism, or a rejection, real or imagined), and in these instances we need to be able to think in order to generate a helpful answer/response, rather than running away.

Therefore, we need to make sure that our cortex, or thinking brain, is fully online, and available to us.

-

Here is an exercise that helps you develop a soothing rhythm of breathing:

One of the most effective ways of doing this is to slow and deepen our breathing.

Sit comfortably and take slow deep breaths. To ensure your breaths are deep you should be able to see your stomach rising and falling as you breath.

Now Start to create a gap between each of your breaths. Breath in slowly and hold your breath for a short time, then breath out and again hold your breath for a short time. In this way you can create four equal parts to your breathing. Breathing in (1), waiting (2), breathing out (3) and again waiting (4) before breathing in again etc.

Meditation

Meditation has been around for thousands of years and can be a good way to start to build a healthy ‘inside’ life. Whilst our lives can be complicated and difficult it is important to remember to focus on the positive things that it is possible for us to be and feel.

Sit comfortably with your hands palm up on your lap. Breathe deeply and slowly as in the breathing exercise above. Spend a couple of minutes getting used to this slow breathing.

Now take your right hand and place it on the centre of your stomach. Say to yourself “I am peace”. See if you can feel the silence and peace of this moment. Spend a few moments with the sensation of peace within you.

Now move your hand to the centre of your chest. Say to yourself “I am love”, “I love and respect myself”. As you breath see if you can feel this love within you. Spend a few moments with the sensation of love within you.

Now place your right hand on the top of your head, palm down. Say to yourself “I am free”. Put your hand back on your lap and spend a few moments concentrating on this sense of freedom within you.

Now see if you can concentrate on the area above your head (above your mind) without thinking. When you are ready you

can open your eyes.

Try to take these feelings with you into your day

Body

You may have noticed that your mood and body posture are somehow connected.

When you feel confident and energetic, you may a have a more upright, open body posture, head up high and comfortably looking people into their eyes.

However, if your mood is low, and you feel vulnerable, ashamed or anxious, you may have noticed that your body seems to shrink and close off, with your head turning down and avoiding eye contact. Some studies have shown that this ‘low power pose’ can increase cortisol and reduce testosterone. This is important as increased cortisol makes us more stress reactive and reduced testosterone makes us feel less

in control.

An upright and open body posture can conversely reduce our cortisol level and increase testosterone, focusing our mind and giving us the confidence to deal with challenges more proactively and skillfully.

People often pay more attention to how we communicate through our facial expression and body posture, than what

we say. Studies show that

when we present with an open and upright posture and establish eye contact, people are more likely to ascribe positive qualities to us and engage with us in a positive manner.

Progressive Muscle Relaxation

Progressive muscle relaxation is a relaxation technique that has found to be helpful for stress, anxiety, reducing pain and improving sleep.

Generally speaking, a calm mind helps relax the body, and a relaxed body signals to our mind that we are safe. PMR involves tensing and then gradually releasing different muscle groups to promote physical and mental relaxation. This practice can help us become more aware of the difference between a tensed muscle and a completely relaxed muscle.

Wear some comfortable clothing. Find a place you be free from disruptions for 10-15 minutes and get into a comfortable position whether you are sitting upright or lying down. Tune into your breath, focus on finding a comfortable rhythm of breathing.

1. Forehead

Squeeze the muscles in your forehead, holding for 15 seconds. Feel the muscles becoming tighter and tenser. Then, slowly release the tension in your forehead while counting for 30 seconds. Notice the difference in how your muscles feel as you relax. Continue to release the tension until your forehead feels completely relaxed. Breathe slowly and evenly.

2. Jaw

Tense the muscles in your jaw, holding for 15 seconds. Then release the tension slowly while counting for 30 seconds. Notice the feeling of relaxation and continue to breathe slowly and evenly.

3. Neck and Shoulders

Increase tension in your neck and shoulders by raising your shoulders up toward your ears and hold for 15 seconds. Slowly release the tension as you count for 30 seconds. Notice the tension melting away.

4. Arms and hands

Slowly draw both hands into fists. Pull your fists into your chest and hold for 15 seconds, squeezing as tight as you can. Then slowly release while you count for 30 seconds. Notice the feeling of relaxation.

5. Buttocks

Slowly increase tension in your buttocks over 15 seconds. Then, slowly release the tension over 30 seconds. Notice the tension melting away. Continue to breathe slowly and evenly.

6. Legs: Slowly

increase the tension in your quadriceps and calves over 15 seconds. Squeeze the muscles as hard as you can. Then gently release the tension over 30 seconds. Notice the tension melting away and the feeling of relaxation that is left.

7. Feet

Slowly increase the tension in your feet and toes. Tighten the muscles as much as you can. Then slowly release the tension while you count for 30 seconds. Notice all the tension melting away. Continue breathing slowly and evenly.

Enjoy the feeling of relaxation sweeping through your body. Continue to breathe slowly and evenly.

The Natural World

It has been known and accepted for a very long time that nature is good for our health and wellbeing and can inspire us with awe and wonder or induce a deep sense of peace and belonging. This idea is found across cultures and has been written about over the centuries by many poets, writers, physicians, teachers, composers and politicians. Why is this? In recent years the scientific evidence for how this happens is mounting up.

In short it is now clear that being in and engaging with the natural world activates our parasympathetic nervous system (our relaxation response), reduces sympathetic nervous system activity (our stress response), improves immune function and has a generally positive impact on our physical and mental health. There are countless studies showing that people who have even the most cursory contact with the natural world have better health outcomes than those who don’t. For example, here are a few of the specific findings:

Phytonicides

These volatile antimicrobial organic compounds released by plants and trees reduce blood pressure, boost immune system functioning and alter autonomic nervous system activity. As well as this they change serotonin profiles and reduce the stress response.

Mycrobacterium Vaccae

Found in soil these organisms show a link to improved immune functioning.

Negative air ions.

Found in high concentrations in forests or mountainous areas and near moving water, these particles have shown a link to reducing depression.

Natural sights, sounds and smells

Seeing, hearing and smelling the natural world reduces sympathetic nervous system activity (our stress response) and increases parasympathetic activity (our relaxation response) and has also been linked to lowering blood pressure and enhancing immune response.

As we can see, there is plenty of research evidence pointing to how the natural world has an overall beneficial impact on our mental and physical wellbeing.

In one study children with an ADHD diagnosis were found to concentrate significantly better after a 20 minute walk in nature as compared to a walk in an urban environment. After the nature walk children with an ADHD diagnosis scored as well on tests for concentration as children without ADHD. Leading to the conclusion that the walk in nature seemed to erase their ADHD symptoms.

If you would like to find out more about the science behind the benefits of the natural world then a great place to start is the web site of an innovative charity called ‘Dose of Nature’:

https://www.doseofnature.org.uk

Try this:

Go for a for a walk in any green space you can get access to.

Find a place to sit down and take in the sights, sounds and smells of your environment. Really focus your attention on the natural world around you. You could even try some slow breathing.

Afterwards notice how you feel.

Re-focus

Thought Suppression

We have a natural tendency to turn away from and supress unpleasant thoughts and feelings. Intuitively, that response makes sense, in that we seemingly are protecting ourselves from discomfort. However, what we know is that the energy we put into pushing something away from us often backfires. The following exercise illustrates this point:

Close your eyes for about a minute. During that time, try your best not to think about the word pink elephant. When the minute is up, share with the person you are working what happened to the pink elephant.

This experience is based on a study in Cognitive Psychology where participants were asked to read a list of words and phrases, one of the them was ‘pink elephant’. Both groups were told to read the list of words, but one group was instructed not to think about the world pink elephant. The participants who were told not to think about pink elephants, reported thinking about this much more than the other participants.

Several studies since have demonstrate that suppressing thoughts tend to do just the opposite. Whilst we will find it very difficult not to think about ‘pink elephants’ or other unwanted images, what we can do is shift our focus of attention. In the next section we’ll look at this in more detail.

Attention

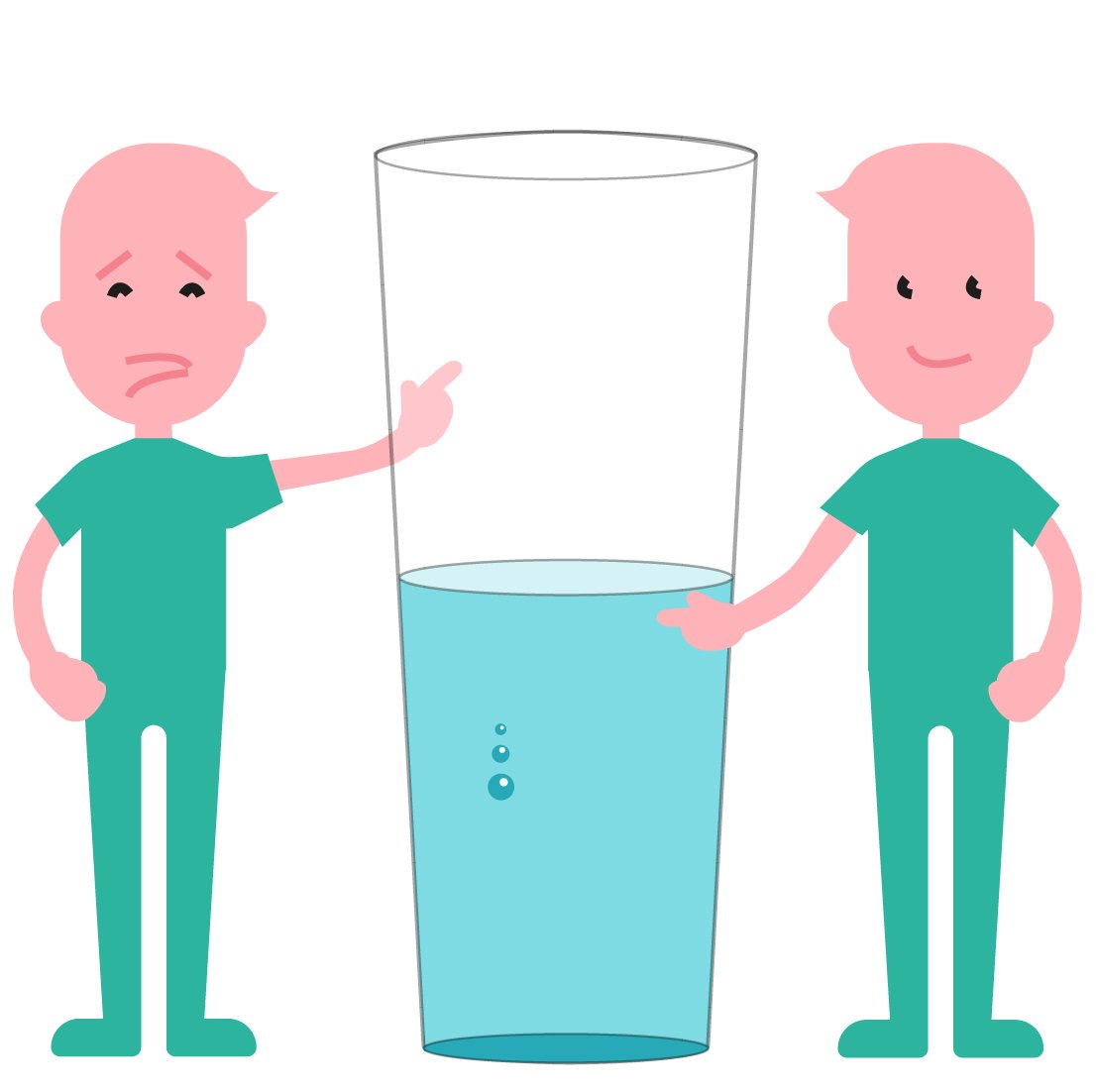

We can think of attention like a spotlight; whatever is under the spotlight gets illuminated and magnified. It appears that we have evolved a negativity bias when it comes to our attention and memory.

The neuroscientist Nick Hanson described this very aptly; ‘the brain is like teflon for positive information and velcro for negative information’. It can seem unfair and unhelpful that negative information can dominate our mind to such an extent.

‘the brain is like teflon for positive information and velcro for negative information’

However, this is linked with survival; our mind will prioritise information about risks and mistakes, as ignoring this could pose a threat to our survival. Although our attention might immediately focus on a threat or a mistake, we have some choice in how we redirect our attention (when safe to do so) onto things that are more helpful/ constructive.

The Power of Imagery

Our brain has an incredible capacity to create images of our external world. In fact these images can be so powerful that simply imagining an event, can be almost as impactful as experiencing it in the present moment.

Some people who have experiences traumatic events may experience distressing memories in the form of flashbacks or nightmares. Simplyremembering these events, activates

the limbic system in our brain, activating the fight, flight and freeze response and flushing our body with stress hormones. It feels like re-experiencing rather than simply remembering the trauma.

Equally distressing can be imagining a future event going horribly wrong, which in a similar way will activate the fight, flight and freeze mode, leaving us in a heightened state of distress.

We can harness the power of imagination and generate or activate positive images and memories that can give rise to feelings of safeness, confidence and hope.

If we bring to mind an image of our favourite meal, we may start salivating as we ‘trick’ the brain into believing

we are about to consume food. In a similar way, we can activate our neuro circuitry to release hormones that can have a calming effect on us.

Safe Place Imagery

The aim of this practice is to create a place in your mind that you can escape to when things are difficult. The first step is to create this place, so use your imagination freely in creating your ideal safe place.

Find somewhere you can sit comfortably, without too much noise or disruption. Get into a comfortable position (upright, open and relaxed), close your eyes and settle into a relaxing rhythm of breathing.

Think of a place where you feel safe and comfortable. It could be anywhere you like, the beach, woodlands, in the mountains or in a house or cabin. Take a good look around you in that place, notice the colours and shapes, what else can you see?

Now notice the sounds around you, or perhaps the silence. Sounds far away and nearer to you. Those that are more noticeable and those that are more subtle.

Then think about the smells you notice there. Next focus on your skin sensations, the ground underneath you, temperature, the movement of air.

Pay attention to the pleasant physical sensations in your body whilst you enjoy your safe place.

Self Compassion

Life can be very challenging and at times feel a bit like an obstacle course. Everyone’s journey through life is unique and the relative fortune and misfortune is certainly not evenly shared out. However, we will all face losses and disappointments, and despite our best efforts and intentions, we will make mistakes and bad decisions.

How we respond

to these difficulties makes a big difference to how much we suffer

The Buddhist parable of the second arrow can help us make sense of suffering and how to manage it.

In this parable it is said that when we suffer misfortune two arrows can strike us. The first of them is the misfortune itself, but the second ‘arrow’ is our reaction to what has happened, the thoughts and feelings that go on within us. Interestingly within Buddhist philosophy the second arrow is oftendescribed as the more dangerous one.

So, if I fall over and really hurt myself, do I blame myself, calling myself and idiot? Or, do I metaphorically give myself a hand up, acknowledging the pain I’m feeling and trying to soothe and comfort myself?

A common observation is that we tend to be more understanding, forgiving andhelpful in response to others’ mistakes than we are towards ourselves when we make the same mistakes.

Most of us have experienced the distress of being blamed for something that isn’t our fault, criticised or put down. We experience these comments and responses as an attack, and our threat system in the brain lights up in a very similar way to these verbal threats as it does in response to a physical threat.

However, research demonstrates that when we launch a verbal self-attack, the effect is the same on the brain, activating the fight, flight and freeze mode. It is certainly helpful to acknowledge and take responsibility for mistakes that we make, however, excessive self-criticism and self-punishment doesn’t help us learn from mistakes, nor does it motivate us to apologise or make amends.

Self-compassion is not about evading responsibility or ‘letting ourselves off the hook’, but developing a kinder, more supportive relationship with ourselves to help us deal with challenges we

face in a skilful way. Sometimes a self- compassionate act requires real courage and discipline, such as giving up reliance on drugs or alcohol to deal with difficult emotions.

Notice your internal monologue. When you are going through a difficult time, maybe after you’ve made a mistake or a bad decision, make a note of what you are saying to yourself. Is it fair/unfair/, helpful/unhelpful?, Kind/ unkind? Enabling/Disabling?

The compassionate Companion

This is another imagery practice that

can be very helpful, particularly if you are going through a particularly tough time or struggling with self-blame and self-criticism.

The idea here is to create an imaginary person who has the compassionate qualities you value. Try not to pick a real person as all humans are fallible, but you can use various compassionate qualities from people you know or have heard about.

Once you have created your compassionate companion and written down their traits or attributes, imagine being in the company of the compassionate companion, paying attention to what it

feels like in your mind and body to have someone given you their full attention. Someone who deeply cares about your wellbeing.

Try filling out the form opposite to create a compassionate companion.

Avoidance

In the same way as we tend to push away and distract from negative thoughts and feelings, we can also get into a pattern of avoiding situations that give rise to this discomfort. The more anxious we feel, the stronger the urge to avoid what is making us anxious. At the time, it may seem like the only possible option, however, by continuously avoiding situations we fear, we tend to confirm our belief that the challenges we face are unsurmountable and that we haven’t got what it takes to deal with these situations successfully.

We may experience that our world shrinks and there are fewer and fewer things we feel confident or comfortable doing. At this point, life can seem pretty gloomy and we may struggle to find a reason to get up in the morning.

The urge to retreat when we are feeling anxious is certainly not unique to humans. Rangers and farmers observed that Bison and domestic cattle that grazed on the vast Rocky Mountain plains in the US had a very different way of responding to a regular storm phenomenon in the area. As the storm travelled from West to East, the Bisons charged into the storm, thereby spending less time in the eye of the storm. In contrast, the domestic cattle, huddled together and anxiously moved away from the storm, but consequently were caught up in the storm for longer periods and were more affectedby it.

We can all benefit from taking a lesson from the Bison in facing our fears head on. We might experience that our negative assumptions don’t materialise and that we cope that little bit better than we had predicted.

Try this:

Write a list of things you would like to do, but avoid doing out of fear of not being able to manage. List these activities in order of difficulty, starting with the least difficult first.

For example, you may be struggling with social anxiety and you would like to build up your confidence to one day being able to go to a gig with friends. Step 1 might be to go to the local shop on your own when it’s quiet, step 2 might be to visit the same place at a busier time. Step 3 may be a visit to a café on your own at a quiet time and step 4 might be to go when its busier.

See if you can identify what’s your number 10 and number 1 and populate the steps in-between. If you break your goals into manageable chunks, youmight find that as you are progressing through the steps, you anxiety lessens, your confidence grows and step 10 might feel within reach. Remember even the smallest steps are progress and will help you to feel less anxious over time.

Belief Systems

As young beings we try to make sense of the world around us. This process of meaning making gives rise to what we

call core beliefs; deeply held ideas of ourselves, others and the world. We use our beliefs to understand and navigate this world, through rules and strategies for living

For example, if we have developed a core belief that crossing a road can be dangerous, we automatically look right and left and ensure the road is clear before we make a swift crossing.

We are particularly impressionable early in life and the words and actions of people in authority, eg., parents, teachers, a close friend, the popular boy or girl in school, shape our core beliefs in important ways. Core beliefs are strongly held and once formed they can be hard to change as they are typically maintained by our tendency to focus on information that supports the core belief and ignoring evidence that contradicts it.

If a parent keeps telling us we are stupid when we were young, this may translate into a strong core belief that persists into adulthood, despite plenty of evidence that we actually are rather capable. We may acknowledge the evidence that we are capable, yet we don’t feel capable because of our fixed core belief.

Often core beliefs develop over time, but they can also change as a result of an isolated incidence. For example, we may conclude from our early life that we are safe and in control and live in a safe world. However, if one day we are the victim on a random, unprovoked attack, immediately, we feel vulnerable and see the world as unsafe and something we need to hide from.

If a young child experiences physical abuse growing up, they may reasonably develop a belief that they are vulnerable, that others can’t be trusted and the world is unsafe. In fact, whilst these things are happening these beliefs are true, which is why they are formed.

Such experiences and the beliefs they cause can give rise to necessary, protective strategies, such as hypervigilance (always looking for danger) and keeping people at arm’s length.

However, once this young child grows up into an adult who can now defend themselves, and may live in a safe environment, these beliefs and strategies may no longer be protective, but act as a barrier to living life fully. In this way, the self-protective beliefs we developed in childhood become self-limiting beliefs in adulthood.

The three P’s of Pessimism;

Personalisation, Permanence and Pervasiveness can play an important role in how we

are affected by the difficulties we experience

Personalisation is thinking that the problem is only due to our own fault or defect, instead of considering other factors that may have played a role in the problem occurring.

Permanence is thinking that a bad situation will last forever, that bad things will always happen and good thing never happen.

Pervasiveness is thinking a mistake or bad situation applies across all areas of your life. For example, “I failed this exam, I fail at everything I do”.

Common negative core beliefs about ourselves include, being unsafe/vulnerable, not being in control, being incapable, not feeling worthy and unlikeable/unloveable. People often develop beliefs that others are judgmental, unkind, uncaring, untrustworthy and we may see the world as unsafe,unpredictable or unfair. We may also develop belief systems about negative thoughts and feelings, which lead us to feel unable to control them.

We tend to act as if our core beliefs are factual and we rarely question the truthfulness and usefulness of these beliefs. However, doing a thorough review of our core beliefs can be helpful as we may be guided by out of date, untrue and limiting core beliefs that give rise to negative thoughts and feelings and unhelpful behaviour and stop us living life fully.

Write a list of beliefs you have developed about:

- Yourself

- The World

- People around you

- Any negative thoughts and feelings

Then think about whether these beliefs are accurate, reflective of your current self and situation, enabling or limiting.

Perspective taking:

Imagine you are walking through town and a good friend walks straight past you, without acknowledging you. What is going through your mind? How do you feel (emotionally and bodily)?

What do you think you might do next? Think about how you might think, feel and act if you made the following conclusion from this situation:

They didn’t see me

They saw me and simply didn’t feel like saying hi

They were going through a particularly tough time and couldn’t face talking to anyone

Often, we make an assumption about a situation or person, e.g., He doesn’t like me, I’m going to mess this up. If these assumptions are left unchallenged, they often convert into ‘facts’.

However, noticing that certain negative thoughts and assumption cause us distress, can remind us to take a step back and questions these thoughts.

Is what I’m thinking/saying to myself true (any real evidence for this?), is it helpful (will it help me deal with the situation more skillfully)? Is it kind? (Would I say this to someone I care about).

Have a look at the list of thinking styles on the next page and see which applies to you. Are there particular situations where these thought patterns are more common for you?

How do these thoughts make you feel? And act?

Try this:

Have a look at the list of thinking styles opposite and see which applies to you. Are there particular situations where these thought patterns are more common for you?

How do these thoughts make you feel? And act?

Thought balancing

Try this work sheet to re-evaluate times where you feel anxious or distressed in some way, there is an example already filled out to help you see how it works:

Building Resilience

You may have had repeated experiences of failure in life, that can contribute to low confidence and self-efficacy (perceived control over our behaviour and social environment)

This in turn may lead you to avoiding challenges and opportunities for learning and growing, as you may expect, or fear, another failure.

In order to build our confidence, motivation and commitment to learning, it’s important to develop positive beliefs about mastery and control. It may be that you struggle

to give up substances, stay in a relationship, attend health appointments etc., but chances are there are some things you do well and consistently,despite many obstacles.

We can also have a tendency to pay more attention to the things we can’t do rather than what we can do. Imagine someone takes their dog out for a walk twice a

day, come rain and shine. They may not necessarily see this as an act of resilience, but in order to persist with this activity, they need to overcome various challenges.

We may be faced with cold, icy or wet weather on occasions, maybe aches or pains some days, or social anxiety and low mood. It can be helpful to identify the strategies that help us overcome these barriers.

Perhaps I’ve got myself some warm, rain proof clothes that I have ready when the weather is bad. I may remind myself that a warm shower and some stretches help ease my aches, and focusing on calming my breathing and brining to mind the smiley dogwalker I always see on my walk helped me feel a little more relaxed.

I may also remind myself that the initial anxiety I feel setting off on my walk, is soon replaced with a sense of achievement and joy seeing the wagging tail of my dog!

We can develop our resilience by applying the strategies we know work for the things we do consistently and apply them to an area of my life where we struggle to stay committed.

List the obstacles you face in committing to your chosen activity and apply your resilient strategies and see if this helps you improve your resilience in this area.

Gratitude

As we have seen, we are very good at focusing in on and remembering negatives, and sometimes an isolated mistakes can ruin an entire day or week. This can affect our mood and motivation and contribute to shaping a pessimistic view of ourself and our surroundings.

A gratitude practice is a good way to help appreciate and remember positive experiences, however, fleeting or trivial they way seem.

Sometimes there may be obvious positives in our day, other times

it may feel like looking for a needle in a haystack. There are no hard and fast rules to doing a gratitude practice.

The idea is simply to spend a little bit of time, perhaps towards the end of the day, to reflect on positives. It may be a positive comment or feedback from a friend, appreciate the warmth of the sun on an otherwise cold, bleak day. Something funny or enlightening you read or heard about.

Sometimes, this includes reframing of a difficult experience; rather than focusing in on a mistake, shift the focus to what you learnt from a mistake, perhaps you responded to this in a creative, skilful manner.

Try this:

Think about a recent day that was difficult for you. First, focus in on negative or difficult aspect of the day and pay attention to how it affects your mood and body. Second, try to focus on anything positive that day and linger with those experiences, notice if you notice a shift in how your mood and body feels.

Relationships

Our relationships have increasingly moved online, something that has been accelerated by the Covid pandemic.

As a result we can easily spend an ever increasing amount of time interacting on various social media platforms.

Clearly there are numerous advantages to being able to connect in this way, however the evidence around social media as a way to connect with others is mixed. Overall evidence indicates that spending extended periods of time on social media might be bad for our mental health.

It appears that the hormones that facilitate good mood (serotonin), motivation (dopamine) and trust and bonding (oxytocin) aren’t released in the same way when we meet through a screen. Further to this one clear risk identified is from platforms with more of a focus on imagery, such as Instagram and Pintrest - where filters and perceived perfection are the 'norm'.

When we are in a bad place, we are more likely to make unfair and unfavorable comparisons with others, comparing our inside experience to the representations of people’s lives posted online. We zoom in on and magnify our perceived inadequacies and compare this to the digitally enhanced photos and inflated profiles on social media, leaving us feeling inadequate and low.

Clearly, social media is here to stay and it brings with it lots of benefits, so the solution may not be to get rid of it altogether. Rather, we perhaps need to ensure that we have time and energy to cultivate relationships face to face and not rely entirely on the virtual world.

As mammals we are hardwired

to connect with our caregivers

Relationships are key to wellbeing, and they can be the biggest source of comfort or trauma. Interpersonal trauma tends to cause more severe and longer lasting distress than accidents and natural disasters.

If we are lucky to have people we can rely on in times of adversity, not only do we recover from psychological trauma quicker, but also our physical recovery is speeded up. This quote from evolutionary psychology illustrates;

‘Bees have evolved to live in a hive and humans have evolved to live in a tribe’

We learn to relate to others by observing how people in our tribe relate to each other and how our primary care givers relate to us.

These relational experiences translate into an inner working model of relationships we call attachment styles. If our caregivers offer protection, comfort and age appropriate autonomy, we are likely to develop what we call a ‘secure attachment style’.

Adults with secure attachment styles tend to feel safe and comfortable sharing feelings with others and able to lean on others in difficult times, but they also have a high degree of self-contentment and self-reliance.

If our caregivers on the other hand don’t offer sufficient protection or comfort, and are dismissive, critical or violent in response to us reaching out for support, we are likely to develop either an insecure-anxious attachment style or an insecure avoidant attachment style.

Someone who is anxiously attached, will often cling on to their partner, fearing that they will leave them. This may result in feeling suffocated and then withdrawal, confirming the belief that people don’t stay.

A person with an insecure-avoidant attachment style, will often keep others’ at arms length, and insist on doing everything themselves, resulting in more fleeting and platonic relationships, leaving the person feeling alone and uncared for.

If we have developed either an insecure- anxious or insecure-avoidant attachment style, it doesn’t mean we can’t develop good, intimate relationships. If we are aware of our attachment style and the challenges this might bring in developing a close connection, we can learn different ways of communicating and relating to others, and as such our attachment style might change over time.

Whether we see ourselves as a natural introvert or extrovert, we all need relationships in order to feel good and function well.

Our relationships can then become a source of comfort and strength

Rat Park

An experiment conducted in the US in the 1970’s called ‘Rat Park’ illustrates the power of relationships;

In this experiment some rats were placed in a cage on their own, with access to two water supplies; one containing pure water, the other containing water laced with either cocaine or heroin.

In a second larger cage, known as rat park, many rats were placed together with lots to do and where they were free to roam, play and socialize as they wished. In rat park

there were also two water supplies, again one with pure water and one mixed with either cocaine or heroin.

The rather remarkable finding was that the rats placed in rat park preferred the plain water, and even when they did drink from the drug laced bottle, they did so intermittently and never overdosed. However, the rats placed in cages on their own preferred the drug laced water, often repeatedly drinking it until they overdosed and died.

In this experiment a positive social community beat the addictive pull of drugs.

Conclusions

Summary

An integral part of being a human is having a brain that is busy sensing and interpreting what’s going on around us, generating a near constant stream of thoughts and feelings, some pleasant others unpleasant

Our inner threat system is working 24/7 to identify and respond to any threats to our survival. These notifications of potential threats will cause momentary stress or anxiety, but a balanced brain is quick to identify false alarms and reassure us we are safe and well. An oversensitive threat system, maybe as a result of past traumas or stressors, struggles to discern between real and false alarm, leaving us in a heightened state of stress

If we struggle to turn off the threat system ourselves, we may resort to substances or activities to temporarily shut the alarm off. However, this is likely to only offer temporary relief, as the stress and anxiety will resurface once we are no longer engaged in the activity.

Although we aren’t able to shut off negative thoughts and feelings altogether, we can practice strategies that help balance our thoughts and calm our emotions, which in turn enable us to feel more in control and make better decisions

Relationships are key to wellbeing

Being able to trust, open up to and lean on others in times of difficulties can help us through adversity. The quality of our relationship with ourself is paramount to good mental health, whether we act as a bully or friend to ourselves when the going gets tough may determine whether we sink or swim.

Evaluation

There is a saying that goes ‘what we measure, we improve’ and this has some backing in the psychotherapy outcome research literature. Measuring our progress or lack of it can help us reflect on what is helpful or not about our intervention, and seeing progress can motivate us to keep going and commit to self-care practises.

The scale below is a composite of various scales that are often used to measure psychological wellbeing and distress in different ways. It is not a validated scale but simply something we have put together to help you track how things are going. So we hope it can a useful tool to track how you are doing or compare before, during and after the work on the Brain Gym manual.